You can read the first part of this blog here.

‘Tibet is the preoccupation of my life from childhood; freedom of Tibet has always been my dream.’ – Tenzin Tsundue.

A Risky Journey to Tibet

As I mentioned in my last blog, my friends and I were looking forward to Tenzin Tsundue’s session about his risky journey to Tibet. Unfortunately, on the final day of Yaanam, October 19th, 2025, due to rain, the open-air events had to be moved indoors. The venue and timings of all other events had to be reshuffled to accommodate this change. Bad luck! Tsundue’s event coincided with the time I had chosen to leave the venue with my friends to have lunch.

However, one of my friends, Prasanth, who attended the session, was kind enough to share a summary with me. He recalled, “At the beginning of the session, Tsundue talked about his parents, who were exiled to India along with the fourteenth Dalai Lama during the China-Tibet conflict times. Tsundue was born in Manali, in North India, where his parents worked as road construction workers. Since it was a chaotic time, his parents couldn’t even record his birthday. Tsundue says he was a restless kid in his childhood; his mother often had to tie him with a rope to stop him from wandering off.

Tsundue completed his graduation from Loyola College in Chennai and his Master’s from Mumbai University. It was in his restless youth, soon after his graduation, that he ventured on a life-changing trip to Tibet to join the freedom movement.

The session was mainly about Tsundue’s journey from India to Tibet, through Ladakh, trekking through the Himalayas and crossing the border. He hoped to learn about the state of his countrymen under Chinese rule and to contribute to the Tibetan freedom movement through this passage. He wandered through kilometres of unpaved roads, camped at lonely sites, and survived severe weather thanks to the help of many kind strangers on the way. Even though he didn’t follow a proper plan or route, he was able to reach Tibet safely. Unfortunately, what awaited him in his country was more unpleasant experiences.

Upon reaching Tibet, the first man Tsundue met, a local Tibetan, tried to rob him of all his money and belongings. When Tsundue threatened to seek the help of Chinese military men from a nearby army camp, the local man promised not to rob him and took him home. However, this man falsely reported Tsundue as an Indian spy to the Chinese army.

Soon, Tsundue was put in Chinese custody, where he was questioned for days. Since the army knew only Chinese, a language Tsundue couldn’t speak, he struggled to communicate his version of the story to them. Tsundue recollected how ironic this incident was. He was in Tibet to join his country’s independence movement against the Chinese, but a fellow Tibetan ratted him out to the Chinese army.

After interrogating him for many days, the Chinese army realised that Tsundue wasn’t a spy of any country, nor was he part of any revolutionary gangs. They reckoned he was just a Tibetan, born in exile, who tried to return to his home country.

The Chinese army ordered him to write an apology. Tsundue wrote a 24-page letter in English, but it was not an apology. Instead, it was a recollection of the sights he saw on the way from India to Tibet, and a mix of scenes from various Indian movies he had seen before. The Chinese army mistook it for an apology, as they couldn’t understand English, and let him off the hook.

Tsundue knew, upon returning to India, he would have to face serious consequences as he illegally crossed the Indian border to reach Tibet. So once he was back in India, he directly reported to the Indian army camp and confessed to his journey to Tibet. In the camp, again, he was interrogated for many days before they let him go.

Tsundue’s protests didn’t end there.

In January 2002, while Chinese Premier Zhu Rongji was addressing Indian business tycoons in Mumbai’s Oberoi Towers, Tsundue scaled scaffolding to the 14th floor to unfurl a Tibetan national flag and a FREE TIBET banner. In April 2005, he repeated a similar stunning one-man protest when Chinese Prime Minister Wen Jiabao was visiting Bangalore.

Tsundue claims that, since then, he has been under the constant observation of Indian intelligence. Whenever a Chinese president or any officials from China visit India, they arrest Tsundue on a precautionary basis, almost like a protocol. So far, he has been arrested 16 times, including the one time in Lhasa, Tibet.”

Hearing Tsundue’s story made me realise the extent of things we take for granted. Ever since I was born, I have called India my home and country. My parents and I always lived under the safety of four walls and a sheltered roof. India’s struggle for Independence was just something I had to read and learn for my exams from textbooks, not something I had to actively participate in or strive for. But Tsundue and his fellow countrymen have been struggling for years to win back their country’s freedom and write that part of Tibetan history.

Tenzin Tsundue’s Poetry

My face lit up with a smile when I realised Tsundue had one more session at Yaanam – the Poetic Trail. In that session, Tsundue, along with other poets Pramudith Rupasinghe and Madhu Raghavendra, read out their various poems inspired by travel. I attended the session with my new friend Latha, a Mysorean on her fourth visit to Varkala.

All three poets who participated in the session were amazing. But maybe because of the conviction in his voice, the subtle power of his simple word choices, or perhaps just because I was already aware of his story, Tsundue’s poetry disturbed me the most. To be honest, it gave me chills. Even Latha, who claimed to be a newbie at poetry recitations and literature festivals, was deeply moved by his poetry.

Like the poem ‘When it rains in Dharamsala’ where he talks about the torturous monsoons beating against the tin roof of his room and flooding it, but also about the tears and despair flooding his eyes and heart:

“When it rains in Dharamsala

raindrops wear boxing gloves,

thousands of them

come crashing down

and beat my room.

…

I cannot cry like my room.

I have cried enough

in prisons

and in small moments of despair.”

Or the poem ‘space-bar A PROPOSAL’ he wrote for his professor:

“your walls open into cupboards

is there an empty shelf for me?

let me grow in your garden

with your roses and prickly pears

i’ll sleep under your bed

and watch TV in the mirror…”

You don’t even have to be a refugee or homeless person to resonate with his words. Even an immigrant, or someone who has lived in hostels, rented houses, or at a relative’s place, would understand that state of never fully feeling at home. A raised voice, a heartfelt laugh, or switching ON an extra bulb could invite the owner’s wrath. At our own homes, it would only lead to a scolding from our parents or grandparents, but in a rented place, you could be evicted for a simple mistake like that. Or you might receive a sermon on how you’re overstaying your welcome. That state of living under constant scrutiny, feeling guilty for our mere presence, for just existing… Tsundue wrapped all these complicated feelings and thoughts into simple but profound lines like ‘I will watch TV in your mirror.’

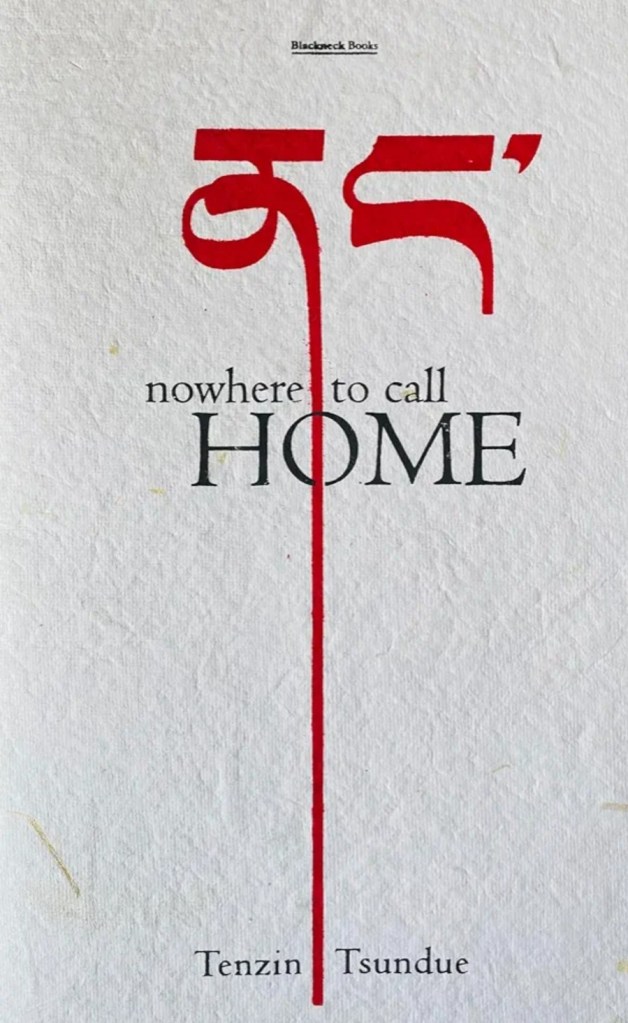

The 45-minute session was not enough to satiate our interest in Tsundue’s poetry, let alone all three of these incredible poets. So at the end of the session, I rushed to the bookstore with Latha and bought the only Tenzin Tsundue book that was available. A short 60-page book named Nang Nowhere to Call Home, written in English and sold for just Rs 50. As Tsundue lives solely from the earnings of his book sales, I wished I could buy more of his books, especially his poetry collection Kora. Later, while exploring his personal website, I stumbled upon a link to download this book for free.

Nang Nowhere to Call Home

“Home is not a house but the purpose that takes us places, and sometimes away from our own home.” – Nowhere to Call Home.

This book is a collection of a few of Tsundue’s essays, poetry, stories, and one interview.

Tsundue’s Political Essays

In Tsundue’s essays in this book, he explores his broken identity as a Tibetan in exile, a refugee in India, and someone with no passport, nationality, or a place to call home.

“Losar is when we the juveniles and bastards

Call home across the Himalayas

And cry into the wire”

On the Tibetan new year, Losar, Tsundue watched his brethren wait in a long line outside a phone booth in MCLeod Ganj, to call their loved ones in Tibet. One by one, they entered the booth, made the calls, and came out, crying and emotionally wrecked, then paid and left. So Tsundue started calling it the Cry Booth, only to realise they were fortunate to have a family to cry to, and a house to call home.

Across the essays, Tsundue talks about the hardship of his countrymen back in Tibet…

“Tibet is now a police state. To mine lithium, copper, gold and rare-earths, China’s mining in Tibet is pushing Tibetan nomads and farmers off their ancestral land, coercing them to relocate to alien and artificial villages, much like how White American colonists transplanted Native Americans into fenced plots called ‘Reservations.’”

…but also about their resilience.

“In seventy years, Mao Zedong’s China became an economic superpower but, in the process, killed its own Buddha. Tibet has lost one sixth of its population and almost all its monasteries, but the People’s Republic couldn’t change us in seventy years. Today, Tibet’s Buddhism may be quietly changing China itself.”

Tsundue also uses his essays as a strong political tool to criticise India’s One-China policy, calling it absolutely lopsided in terms of diplomacy. He claims:

“India has to remain silent on sixty per cent of the contested area under China’s territorial control, and also Hong Kong and claims over Taiwan, while China has to stand with India only on Kashmir. And it does this, too unfaithfully…”

Tsundue also points out that

“It(India) can’t validate its claim over Arunachal Pradesh without recognising the historical independence of Tibet.”

“The Tawang region, the birthplace of the Sixth Dalai Lama, was part of Tibet until the agreement in 1914 resulted in the McMahon Line. This bifurcated the entire region of Tawang and made it a part of British India, with maps redrawn and documents signed.

…

Against this backdrop, how does India hope to validate its claim over Arunachal Pradesh without recognising Tibet, which gave away Tawang to India?”

Tsundue also reminds us that India never had any borders with China, but with Tibet.

“India never had any borders with China; it was only after the Chinese occupation of Tibet that China appeared over the Himalayas. Neither the media-crafted narrative nor the organised education system gives any clear picture about Tibet – what lies behind the Himalayas, the real civilisational neighbour with whom India shares a 4,085 km border.”

Most of his political essays were enlightening, but I found myself vehemently shaking my head ‘no’ while reading the essay ‘Not Playing With Fire: Acts of suffering for the awakening of others,’ in which he talks about self-immolation as an act of protests among Tibetans.

Tsundue’s Short Stories

The book also contains two heartwarming stories written by Tsundue.

In ‘Zumki’s Snowlion,’ we meet a young girl named Zumki who wants to meet the snow lion. “It is believed that only the most kind and those with the purest of hearts can see a snow lion.” It made me wonder: Will a snow lion ever show up before me? Are we pure and kind enough for that?

In the short story Kora, we meet a young Tashi who accuses a Tibetan elder: “You were the people who gave away our country into the hands of the Chinese.” But when the elder retorts, “If my son had been alive, he would have been older than you. But he died fighting the Chinese. He died in my lap. … You tell me what you have done for Tibet up to now?”, just like Tashi, we fall silent too.

Minimalist Lifestyle

Apart from Tsundue’s writing and protests for Tibet’s Independence, what inspired me the most was the simple lifestyle he lived. Quoting his friends:

“He lives in simplicity – living in two sets of Tibetan shirts and jeans, and always carrying this worn-out backpack, stitched and patched, and adorned by old stickers and trinkets. In that, he carries his daily tools and his cherished poetry books. Behind this minimalist existence lies a deep well of strength, integrity, and commitment. While many seek comfort or recognition, Tsundue has chosen a path of sacrifice. He makes do with his simple life, a vegetarian and teetotaler, solely out of the sales of his self-published books.”

– Tashi, Jana, Mata Gyamtsi and Alfie, from Prague, Czech Republic, Preface, Nang Nowhere To Call Home.

Tsundue’s Longing For Home

Though there was so much to learn and be inspired by Tsundue’s life, the realist in me couldn’t help but doubt how practical his dreams were. We live in a world where not just the governments, but also individuals serve their own selfish agendas over the common good. A selfless and peace-loving community like Tibetans are no match for the economic and military superiority of China. Even India, despite being the largest democracy in the world and providing refuge for the Tibetan exiles for decades, cannot be expected to risk the peace and safety of its 1.46+ billion people to officially recognise the independence of Tibet, and thereby anger China further, especially given the existing tensions between the two countries over Arunachal Pradesh.

The pessimist in me, for a split second, even equated Tsundue’s longing for Tibet as Hiraeth. Hiraeth is a Welsh word that means homesickness for a home that never was and never will be. I was thinking along the lines of… Tsundue has never been to his home in Tibet. Will the Tibetan independence movement bear fruit in his time? Will he be able to build a home there someday? Does Tibet stand a chance against the powerful China?

But Tsundue has sharp replies for such pessimists, too:

“Home for me is real. It is there, but I am very far from it. It is the home of my grandparents and parents left behind in Tibet. It is the valley in which my Popo-la and Momo-la had their farm and lots of yaks, where my parents played when they were children.”

And he retorts:

“Gandhi too must have been asked the same question: ‘Gandhi, do you stand a chance?’ Looking at the British Empire ruling two-thirds of the world and arrogantly saying ‘The Sun never sets on the British Empire’. Today the entire UK can fit in Rajasthan, only one of 28 states of India. EMPIRES COME AND GO. For India, it took 200 years…”

“…Our country(Tibet) may not be free today, but we are, in our hearts. And one who has freedom in the heart will remain free. Of course, Tibet will be free, Inshallah.”

When an entire nation in exile is putting its hope on this freedom movement, who are we to discourage them with our own cowardice and pessimism? I commend their audacity to hope, their daily sacrifices for the cause of Tibetan freedom, their willpower and courage.

As the old man says to Tashi, we can only hope and pray that the younger Tibetans will ‘complete the work left incomplete, will be successful in the struggle and take His Holiness the Dalai Lama back to a free Tibet.”

Personally, I made a mental note to correct my own misconceptions. What Tibetans feel towards Tibet is not a homesickness for a home that never was and never will be. Tibet was, and Tibet will be. And Tibet still is in the hearts of every Tibetan who calls it their home.

Author’s Notes

~ All quotations used in this post are from Tenzin Tsundue’s books Kora and Nang Nowhere to Call Home.

~ All other content on this book review is the intellectual property of the author. © 2025 Lirio Marchito. All rights reserved.

~ You can read all the blogs in the Yaanam 2025 series here: Yaanam2025.